IECE Transactions on Social Statistics and Computing

ISSN: 2996-8488 (Online)

Email: [email protected]

Throughout history, cooperation between China and Central Asian countries have persisted for an extensive duration, particularly in the domains of trade and culture. In the prosperous period of the Ancient Silk Road, Central Asia functioned as a vital link connecting Eastern and Western civilizations. It was not only a crucial hub for commercial trade, but also an important place for financial and industrial activities. However, with the advent of the age of the Great Geographic Discoveries, the fast-paced expansion of sea routes caused a significant transformation in the flow of global trade, gradually shifting from land routes to sea routes [1]. Central Asia then became part of the Russian Empire during the latter part of the nineteenth century. After the October Revolution, union and constituent republics were established in the region, which eventually became part of the Soviet Union. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the five Central Asian states declared their independence. This historic transformation initiated a fresh phase of cooperation between China and the Central Asian countries across various domains, such as economy, politics and cultural exchange.

Within the scope of this study, Central Asia is defined as the five countries that gained sovereignty after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, namely Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. These countries are often viewed as a distinct region with unique characteristics due to their similar historical backgrounds and close geographic proximity. The region of Central Asia has evolved into a strategic location where global and regional powers compete for influence. For China, considering its extensive shared border of over 3,300 kilometers with Central Asian countries, deepening cooperative relations with Central Asia is strategically important on a number of levels: not only does it contribute to preserving regional peace and stability, but it also plays a role in diversifying energy supplies, securing transportation corridors to the west, and promoting mutual prosperity and development [2].

In 2013, while visiting Kazakhstan, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed the initiative of jointly building the “Silk Road Economic Belt”, which marked the beginning of a new chapter of cooperation between China and Central Asian countries under the framework of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Trade cooperation between China and Central Asian countries is a key component in the building of the Silk Road Economic Belt. This study selects trade statistics for the period from 2013 to 2023 and analyzes in-depth the trade exchanges between the two sides, aiming to thoroughly comprehend the status quo, challenges and prospects in China’s trade interactions with the five countries. This research enables a clearer identification of the trade collaboration potential and prospects for trade cooperation between the two sides can be more clearly recognized, providing insights for further promoting economic cooperation.

While exploring the contours of economic cooperation, a crucial approach is to analyze trade data, particularly imports and exports. This data enables the mapping of trade trends, the identification of key trading partners and the highlighting of specific areas of concern. The analysis spans from 2013 to 2023, allowing for a thorough review of the past ten years.

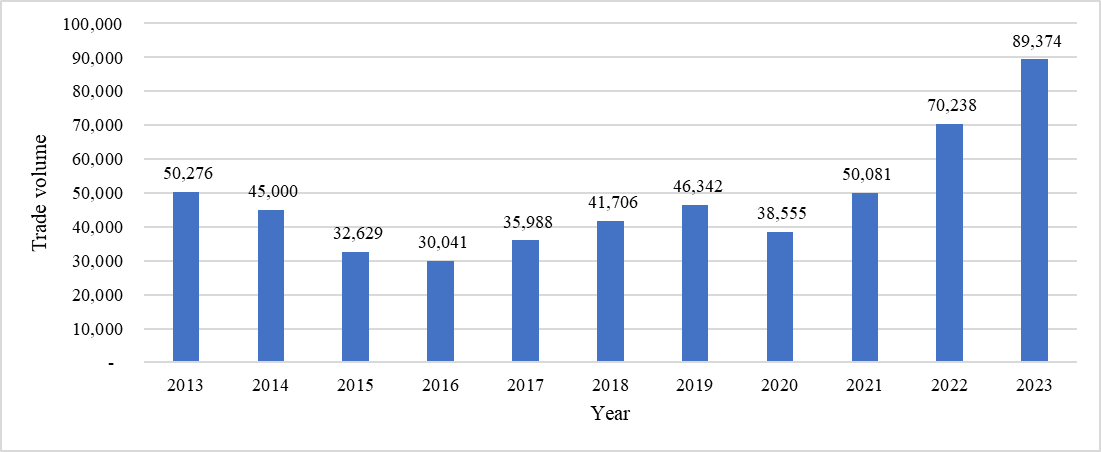

In the autumn season of 2013, a series of diplomatic visits were conducted by the Chinese President to Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. During his visit, President Xi presented an important speech at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan entitled “Promote People-to-People Friendship and Create a Better Future”, advocating the adoption of a new mode of cooperation to jointly advance the development of the Silk Road Economic Belt [3]. Since 1992, when China formally established diplomatic ties with the countries in Central Asia, bilateral economic and trade relations have grown steadily. The year 2013 witnessed a historical peak in commercial relations between China and the five countries, with their total trade volume exceeding the milestone of USD 50 billion. This milestone underscored the productive and mutually beneficial nature of their trade cooperation.

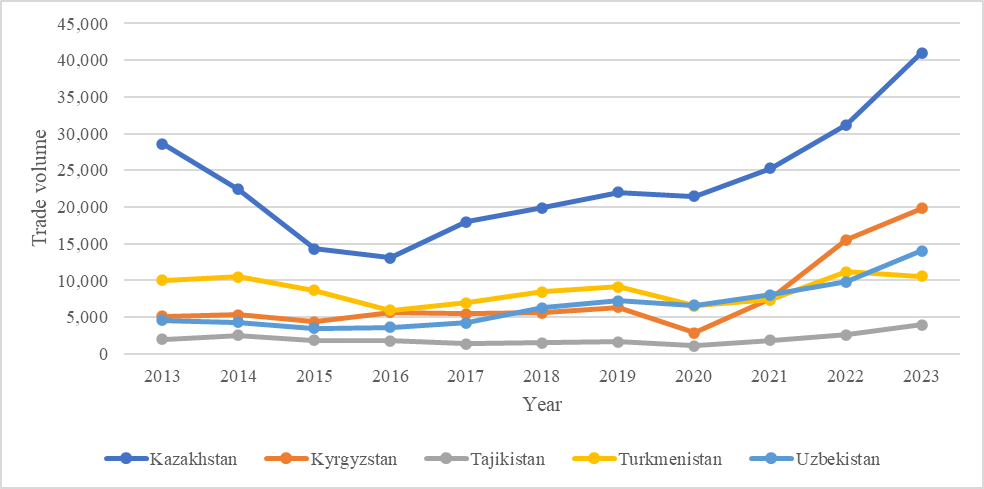

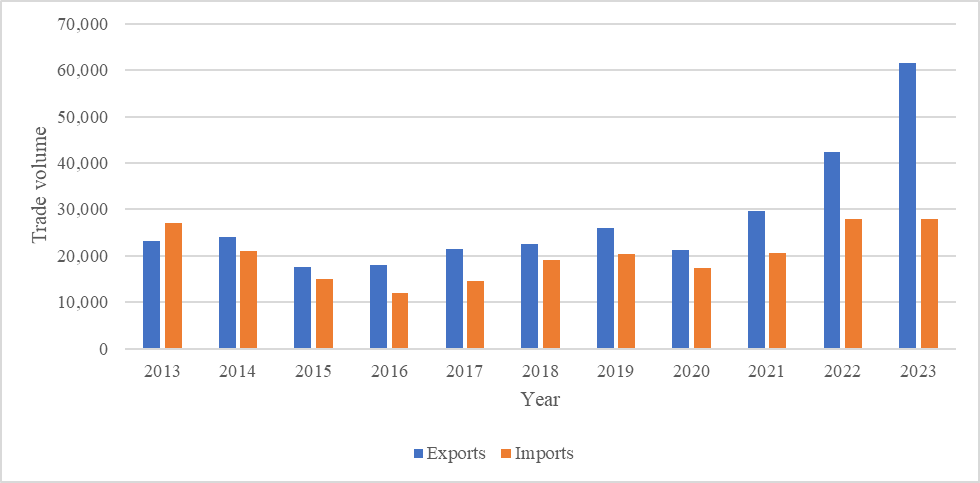

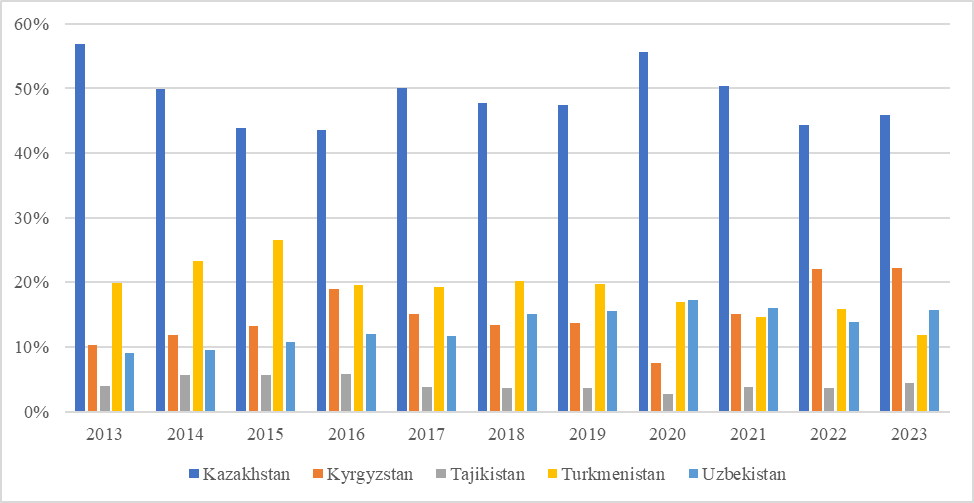

In 2014, however, the global economic resurgence progressed at a slow pace and faced many challenges, with international market experiencing weak demand, which directly affected the growth momentum of global trade. Under such a macro background, China’s trade exchanges with Central Asia were also affected accordingly. In addition, the outbreak of international events such as the Ukraine crisis in 2014 triggered volatility in the international market prices of commodities including crude oil and natural gas, which in turn affected the trade volume between China and Central Asian countries. After reaching a high point in trade volume in 2013, China’s trade volume with Central Asian countries has shown a downward trend (see Figure 1 for details). In particular, the decline has been particularly significant in China-Kazakhstan trade, with the trade volume decreasing significantly from USD 28.6 billion in 2013 to USD 13.1 billion in 2016 (see Figure 2).

Between 2017 and 2019, trade interactions between China and Central Asian countries gradually warmed up. However, amidst the worldwide pandemic of COVID-19, the ensuing transportation restrictions and border closures hit trade cooperation between the two sides to some extent. This change led to a decline in China’s trade with Central Asian countries to USD 38.6 billion in 2020, down from USD 46.3 billion in 2019 (see Figure 1). Despite the challenges, the two sides, through joint efforts, had been able to quickly rebound their total trade to USD 50 billion in 2021 (see Figure 1), a rebound that amply demonstrates the resilience and adaptability of China-Central Asian trade cooperation.

The year 2022 saw a major online summit, which was successfully held to celebrate the 30th anniversary of diplomatic ties between China and countries of Central Asia. This event was the first high-level meeting involving heads of state from China and the five Central Asian states. At the meeting, President Xi declared that China would “import more quality goods and agricultural products from countries in the region, continue to hold the China-Central Asia economic and trade cooperation forum, and strive to increase the trade between the two sides to USD 70 billion by 2030” [4]. Surprisingly, this goal was reached ahead of schedule in that year. In 2022, the aggregate trade value hit an unprecedented high of USD 70.2 billion, exhibiting an annual growth rate of over 40%, a figure that is a hundred times higher than the trade volume at the beginning of the inception of diplomatic ties between the two sides (see Figure 1). The data presented in Figure 1 also shows that trade cooperation between the two sides hit a fresh peak in 2023, with trade volume reaching USD 89.4 billion, and the annual growth rate remaining at a high level of 27%. This series of data not only highlights the deep potential of cooperation between the two sides, but also creates a robust foundation for the sustained growth in bilateral trade ties in the years to come.

A review of the trade data for the period from 2013 to 2023 indicates that the scale of trade between China and Central Asian states is subject to ebbs and flows, rather than following a uniform upward or downward trajectory, showing the dynamic and complex nature of trade relations.

Central Asia holds significant strategic value for China not only as the birthplace of the Silk Road Economic Belt, but also as a place where the BRI was proposed, as well as occupying a large market share among China’s western neighbors. Although the degrees of trade reliance between China and the five countries of Central Asia varies and their share in China’s overall foreign trade is not significant, they play an indispensable role in guaranteeing Chin’s energy security, promoting the high-quality BRI cooperation and advancing its neighborhood diplomacy.

According to official figures from China’s General Administration of Customs, the total trade volume between China and the five countries had shown an overall growth over the decade, especially in the trade with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. As revealed in Figure 2, China’s trade with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in 2023 realized an increase of 32.2% and 28.8%, respectively, compared to the previous year. Trade with Uzbekistan increased by 44.9%, while trade with Tajikistan grew most rapidly, by 53.5%. Although Tajikistan’s trade with China is relatively small among the five Central Asian countries at USD 3.93 billion, the growth momentum cannot be ignored. As an economic powerhouse in the Central Asian region, Kazakhstan continues to hold its position as China’s most important trading partner in Central Asia, with total trade between the two sides reaching USD 41.02 billion in 2023, followed by Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan.

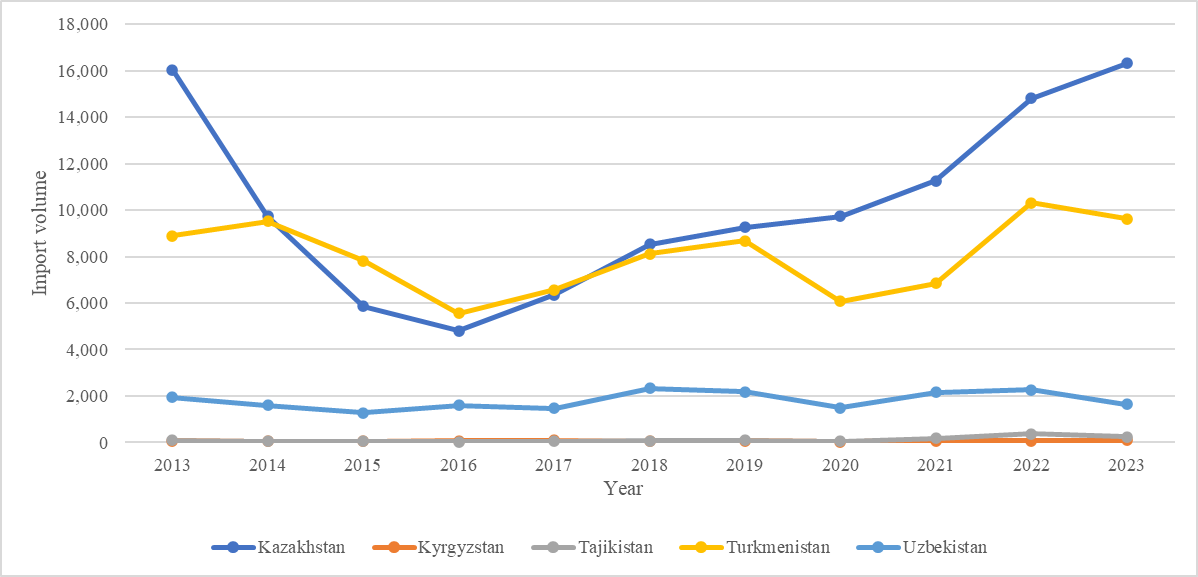

As shown in Figure 3, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are the main sources of China’s imports in Central Asia. China’s imports from Kazakhstan experienced a significant decline after 2013, but began to show a recovery after 2016. Imports are concentrated in four key areas: energy resources (e.g., crude oil and natural gas), metals and their minerals (e.g., refined copper and copper ore), nuclear energy-related chemicals (e.g., uranium compounds), and agricultural by-products (e.g., wheat). Imports of these commodities holds strategic significance for ensuring China’s energy security and resource supply, while also contributing positively to enhancing bilateral trade relations and economic cooperation between China and Kazakhstan. Turkmenistan, a major exporter of natural gas and piped gas, serves as an essential component in realizing China’s energy import diversification. China’s import trade from Turkmenistan shows some volatility, which may be related to factors such as fluctuations in the international energy market, price changes, and supply and demand. Over the ten-year period from 2013 to 2023, China’s import trade from Uzbekistan has remained relatively stable at about USD 2 billion. China’s main imports from Uzbekistan include mineral fuels, copper and its products, cotton and yarn. Meanwhile, China’s imports from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan were relatively small, which may be related to these countries’ industrial structure, export capacity, and trade agreements with China. These trade data not only reveal the complexity of trade relations between China and Central Asian countries, but also reflect China’s active participation in economic cooperation in the region.

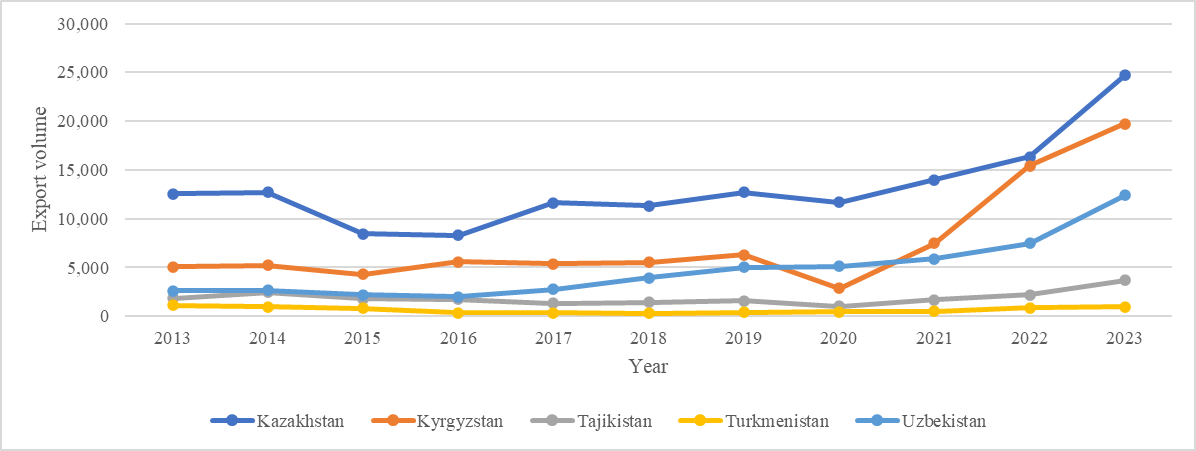

As illustrated in Figure 4, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan serve as primary markets for China’s export activities within Central Asia’s international trade landscape. China’s export portfolio to Kazakhstan spans multiple industrial sectors, including electromechanical products, textiles and audio-visual equipment, among others. Among these exports, machinery and equipment occupy a prominent position. For Kyrgyzstan, China’s exports to it showed a remarkable recovery trend after the trade trough in 2020 due to COVID-19, with exports surging from USD 2.9 billion in 2020 to USD 19.7 billion in 2023. The exports from China to Kyrgyzstan include machinery and equipment, electronic goods, automobiles and their accessories, chemical products, construction materials, medical equipment and pharmaceuticals, which directly respond to the country’s development needs in the areas of infrastructure construction, transportation and healthcare. Since 2016, China’s exports to Uzbekistan have shown a year-on-year growth trend, from USD 2 billion in 2016 to USD 12.4 billion in 2023. China’s main exports to Uzbekistan include machinery and equipment, electrical appliances, vehicles and their parts, textiles and other products. It is particularly worth mentioning that new energy vehicles have become an emerging bright spot in trade between the two countries. Tajikistan ranks the fourth-largest export market for China in Central Asia, with key exports comprising machinery products, daily necessities, footwear and auto parts. In contrast, the exports from China to Turkmenistan are smaller in scale, with the main categories of exports involving machinery products, consumer electronics and steel products.

For the Central Asian countries, China serves both a reliable business partner and a crucial buyer of energy, raw materials and agricultural products, and is therefore seen as an ideal trade partner. China’s position as a major market and key trade and investment partner among neighboring Central Asian countries has a significant impact on the steady growth of their economies. Specifically, data from the Statistics Agency under the President of Uzbekistan shows that China overtook Russia to become Uzbekistan’s largest trading partner in 2023 [5]. In the same year, China also stood as Kyrgyzstan’s leading trading partner, contributing to 34.7% of the country’s total foreign trade [6]. In addition, according to Kazakhstan’s Bureau of National Statistics, China held the position of Kazakhstan’s top trading partner in 2023 [7].

Currently, the main challenges facing China and Central Asian countries in trade cooperation relate to several key aspects, including the problem of trade disparities, weak trade facilitation and the risks posed by geopolitical factors, which need to be brought to the attention of both sides.

Trade exchanges between China and Central Asian states show obvious imbalance in both scale and structure. The imbalance in the scale of trade is mainly manifested in two aspects. On the one hand, since 2014, China has consistently maintained a trade surplus in its trade relations with the other side (refer to Figure 5). In other words, China’s exports have been consistently higher than its imports from these countries. This chronic trade imbalance has caused Central Asian countries to become increasingly dependent on the Chinese market.

On the other hand, there are significant differences in the scale of trade between China and the five Central Asian countries, which reflect differences in resource endowments, levels of economic development, and geo-economic linkages with China, as revealed in Figure 6 [8]. The scale of China’s trade with Kazakhstan is substantial, in contrast to the relatively small scale of trade with other Central Asian countries. Although China’s trade with Tajikistan has grown from USD 1.958 billion in 2013 to USD 3.926 billion in 2023, this amount is still the lowest among the five Central Asian countries. This unbalanced trade distribution poses a challenge to further optimize China’s trade cooperation with the five countries.

In terms of trade structure, the interaction between China and the five countries shows some imbalance. Previously, China’s exports to Central Asian countries primarily consisted of garments and daily consumer goods, but since 2013, the proportion of electromechanical products in China’s exports to Central Asian countries has grown significantly, which has had a significant impact on the industrial upgrading and the development of the processing and manufacturing industries in Central Asian countries. Meanwhile, the commodity structure of China’s imports from these countries has gradually expanded from mainly resource and energy products to non-energy sectors including agricultural products and manufactured goods, indicating that China is becoming a key and stable market for Central Asian countries seeking to diversify their exports [9]. However, despite the improvement in the structure of China’s trade with Central Asian countries, it still faces a number of challenges. The economic structure of Central Asian countries is predominantly resource-dependent, and differences in resource endowments between countries have led to imbalances in development. China’s trade structure with Central Asian countries remains relatively homogeneous, with energy trade dominating. In the first quarter of 2023, for example, China’s imports from the five countries were mainly energy products such as coal, crude oil and natural gas, with imports amounting to USD 4.48 billion, accounting for 55% of China’s total imports from these countries [10]. This data highlights the monolithic nature of the trade structure between the two sides and the need to further diversify cooperation.

For the past few years, some progress has been made in enhancing trade facilitation in Central Asia, but the overall potential has not yet been fully realized. Despite recent improvements, trade-related legislation in the region remains unclear and inconsistent, and the dissemination of relevant information is inadequate. In addition, the digitization and automation of trade processes has been slow. Countries have shown shortcomings in cooperation between domestic and foreign border agencies [11]. These challenges limit the further development of trade facilitation in Central Asia.

When exploring the development of commercial interactions between China and Central Asia, trade facilitation should not be overlooked, as it has become an obstacle to the depth of cooperation between the two sides. Although some progress has been made in reducing trade barriers bilaterally, a series of problems, including tariff and non-tariff barriers, still exist, and difficulties in the customs clearance process continue to impede further trade facilitation. In particular, the fact that some Central Asian countries are not yet World Trade Organization (WTO) members poses an additional challenge to trade cooperation between the two sides [10]. Specifically, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have not yet obtained WTO membership, a status quo that may limit the scope and intensity of trade cooperation in the region with China. For Uzbekistan, Deputy Prime Minister Jamshid Khodjiev, who is also Chair of the Inter-Agency Commission on WTO Accession, made it clear at the eighth meeting of the country’s WTO Accession Working Party that Uzbekistan remained an unwavering dedication to its accession process and actively made every effort to achieve substantial advancement, targeting completion before the 14th WTO Ministerial Conference in Cameroon in 2026 [12]. Turkmenistan, on the other hand, is lagging behind in this regard, and despite the formation of the country’s WTO accession Working Party on February 23, 2022, it has not yet been able to convene its first meeting, demonstrating its slow pace in advancing the WTO membership process [13].

According to the Global Risks Report 2024, the world will face risks from multiple dimensions in the next two years, including economic, environmental, geopolitical, social and technological [14]. By definition, geopolitical risk can be understood as “the threat, realization, and escalation of adverse events associated with wars, terrorism, and any tensions among states and political actors that affect the peaceful course of international relations” [15]. Central Asia typifies this geopolitical risk profile.

|

|

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | 2005 | 2011 |

|

||||||

| Uzbekistan | 2012 | 2016 |

|

||||||

| Kyrgyzstan | 2013 | 2018 |

|

||||||

| Tajikistan | 2013 | 2017 |

|

||||||

| Turkmenistan | 2013 | 2023 | / |

The geopolitical importance of the Central Asian region has grown significantly in recent years, a change that has been influenced primarily by such major international events as the withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan and the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. A number of global and regional players are actively seeking to expand their influence in Central Asia. These players have realigned their policy objectives and means of implementation in the region with their strategic interests. As for Central Asian countries, they are actively seeking a new role on the international stage, seeking to position themselves as a “intermediate zone” through “corridor diplomacy” and “multi-vector diplomacy” [16]. This approach is aimed at enhancing the strategic position and influence of the Central Asian countries by strengthening regional cooperation and multilateral relations. In this context, the competition among major powers, historically known as the “Great Game”, has had an indirect effect on China’s economic and trade relations with Central Asian countries. While strengthening economic ties with Central Asia, many countries and international entities are actively expanding their influence in this key region. This has led to China’s trade relations with Central Asia becoming more intricate and unpredictable. Therefore, China needs to take into account these external factors and their possible impact on regional stability and economic cooperation when advancing its economic and trade cooperation with Central Asian countries.

Within the region, cross-border conflicts pose a major threat to lasting peace and security in the region. A surge in nationalism has coincided with growing assertions of sovereignty. Tensions among Central Asian states have been evident in incidents such as the border clashes between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in April 2021 and September 2022, which resulted in significant loss of life [17]. These events not only raise deep concerns about humanitarian issues and regional security, but may also have a negative effect on China’s economic and trade cooperation with Central Asian countries. Taken together, geopolitical risks in Central Asia are reflected not only in inter-state tensions and rivalry among the major powers, but also in the potential threat of terrorist activity. These risk factors challenge the region’s security architecture and social stability, with enduring consequences for trade and economic cooperation.

Looking ahead, the enhanced China and Central Asian political ties, the deepening of infrastructure connectivity and the growth in e-commerce are expected to give new impetus to trade ties between the two sides and reduce the abovementioned challenges to some extent.

The BRI, together with China’s partnerships with Central Asian states, has undoubtedly built a solid foundation for bilateral trade exchanges and economic collaboration. Specifically speaking, China and the five countries have developed strategic partnerships at various levels, as shown in Table 1. These partnerships have not only provided policy support and directional guidance for collaboration in core sectors like trade and investment, but have also facilitated the realization of win-win scenarios.

Additionally, high-level mechanisms between China and the Central Asian countries are vital in promoting practical cooperation. These high-level mechanisms encompass gatherings such as the Summit on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), the meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), as well as state visits by leaders [18]. In the third decade of the 21st century, a new chapter in China’s diplomatic relations with the Central Asian countries began. 2020 marked the milestone of the first foreign ministerial-level meeting between China and the Central Asian countries, which has since become a regular mechanism, with economic cooperation and trade exchanges at the center of the agenda [19]. By June 2022, at the third China+Central Asia (C+C5) Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Kazakhstan, an important consensus was reached on the establishment of the heads of state meeting mechanism of China+Central Asia (C+C5) [20]. Immediately following in 2023, the first China-Central Asia Summit was successfully held. During the summit, President Xi comprehensively outlined China’s foreign policy toward Central Asia, and a consensus was reached, in collaboration with the leaders of all five Central Asian countries, to build a closer China-Central Asia community with a shared future. Meanwhile, the mechanism of meetings between the heads of state of China and Central Asian countries was established, and a permanent secretariat for the China-Central Asia mechanism was set up [21]. The official launch of the secretariat for the China-Central Asia mechanism has provided effective implementation guarantees for the agreements reached by the two sides in the field of economy and trade, and has promoted high-quality progress in economic and trade cooperation. In addition, China’s Ministry of Commerce and the economic and trade authorities of Central Asian countries jointly launched the China-Central Asia Meeting Mechanism of the Ministers of Economy and Trade in April 2023 and signed a number of multilateral documents aimed at deepening cooperation in the fields of economy and trade, digital economy, infrastructure construction, etc., which marks a solid step forward in practical economic and trade cooperation.

The landlocked nature of Central Asia adds a layer of complexity to its trade interactions with global markets. The high cost of international trade logistics has become a notable obstacle to the region’s international trade. As the fervor for resource-dependent growth models wanes, Central Asian governments are gradually recognizing the need to promote economic diversification. In this context, strengthening infrastructure development, especially land-based trade routes across the Eurasian continent, has become key to fostering new export-oriented businesses. In order to expand non-traditional exports and enhance connectivity, Central Asian countries must take steps to simplify business processes and ease the burden of cross-border trade. This means focusing on physical infrastructure development, upgrading interregional connectivity, lowering barriers to the transportation of goods, and stimulating broader international commerce [22]. Through such measures, the five Central Asian states could increase their global trade competitiveness and inject new dynamism into their economic development.

The BRI prioritize connectivity of infrastructure, which will help to alleviate the shortcomings in the infrastructure of the Central Asian region. The China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor (CCAWAEC), as an essential economic and transportation artery under the framework of BRI, starts in northwestern China, crosses Central Asia, and extends westward to the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Peninsula and the Mediterranean coast. Along CCAWAEC, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Highway has been fully open to traffic, China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline has also been put into operation, and the grain and oil rail transit lines from North Kazakhstan to China has been synchronized with the operation of the China-Europe Railway Express [24]. China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway is another noteworthy project, which serves as a strategic connectivity project between China and the region, and a flagship endeavor of BRI cooperation among the three countries. In June, 2024, a trilateral intergovernmental agreement on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway project was signed in Beijing, marking substantial progress in this project. The ceremony was attended by Chinese, Kyrgyz and Uzbek leaders via video link [23]. The completion of the project is expected to shorten the transportation distance from China to Europe and the Middle East by about 900 kilometers and reduce the transportation time by seven to eight days. The construction of transportation infrastructure under the BRI is expected to reduce trade costs along the CCAWAEC by approximately 10%, signaling that future trade links between China and Central Asia will be further strengthened by infrastructure connectivity [24].

E-commerce activities refer to the buying and selling of products and services through internet platforms, including various forms of digital transactions such as direct consumer purchases, B2B transactions, and online virtual transactions. Such mode of trade is able to partially avoid geopolitical risks and reduce reliance on traditional trade routes. According to a professional assessment by IMARC Group, an international research and consulting company that specializes in market assessments, the e-commerce market size in Central Asia reached USD 11.1 billion in 2023. The IMARC Group forecasted that the e-commerce market size in the region is expected to increase to USD 147.4 billion by 2032, with an estimated increase rate of 32.2% between 2024 and 2032 [25]. The notable increase in online retail is primarily driven by the COVID-19 outbreak, which has caused a rise in digital marketplace usage. Meanwhile, increased acceptance of e-commerce among consumers and merchants (e.g., increase in Internet coverage and number of online shoppers) and expansion of cross-border e-commerce opportunities are also key drivers of the e-commerce market’s growth in Central Asia. Some experts believe that Central Asian countries have the potential to expand e-commerce’s share in their trade to 20% by 2030 [26]. Currently, the Central Asian e-commerce market is highly competitive, and among the many players, AliExpress, the online retail platform of Hangzhou, China-based Alibaba Group, has emerged as one of the major competitors in the market.

Acknowledging the promising future for e-commerce expansion in Central Asia, China and the region’s countries are enhancing their collaboration in the e-commerce sector. According to the Joint Statement Between Leaders of China and the Five Central Asian Countries on the 30th Anniversary of the Establishment of Diplomatic Ties, the parties have reached a consensus to strengthen collaboration in the e-commerce sector and establish a “China-Central Asia dialogue mechanism on e-commerce cooperation” in a bid to develop the “Silk Road E-commerce” [27]. As an innovative effort of the BRI cooperation in the digital era, the “Silk Road E-commerce” is regarded as the new blue ocean of cross-border e-commerce [28]. Kazakhstan, for example, has expressed its willingness to strengthen cooperation and establish a pilot zone for “Silk Road E-commerce”. Kazakhstan has set up national pavilions on China’s two major e-commerce platforms, Alibaba and JD.com, and is actively preparing to open a Kazakhstan pavilion on the Douyin platform to further expand its e-commerce business in China [29]. These efforts mark a substantial step forward in China-Central Asian e-commerce cooperation, paving the way for new market opportunities for enterprises on both sides.

Located at a strategically important crossroads, China supports Central Asia’s role as a major transportation hub in Eurasia. Despite a fluctuating trend, China’s trade volume with Central Asian countries expanded from USD 50.3 billion in 2013 to USD 89.4 billion in 2023. China remained the top-ranking or key trading partner of all five Central Asian states. Meanwhile, among these Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan consistently ranked first in trade with China, while Tajikistan was fifth. The ranking of the other three countries in Central Asian was constantly changing.

At present, trade cooperation between China and Central Asia has encountered a series of challenges that need to be taken seriously and addressed with appropriate measures. Among them, trade imbalances are particularly prominent in terms of scale and structure. At the same time, trade facilitation is not as robust as it could be. Geopolitical risks also endanger the solidity and growth of China-Central Asia trade cooperation. Nevertheless, the future holds promise for the two sides. On the one hand, by enhancing political ties, more mutually beneficial trade agreements can be facilitated. On the other hand, improving connectivity is the key to promoting trade ties between the two sides. Better infrastructure connectivity will greatly reduce trade costs and improve efficiency. In this regard, BRI has significantly enhanced the transportation and energy infrastructure in Central Asia. Meanwhile, the rise of e-commerce presents a particularly exciting opportunity for trade cooperation. By focusing on enhancing political relations, improving infrastructure connectivity, and embracing the potential of e-commerce, China and the five Central Asian states are expected to take trade relations to new heights and contribute positively to the region’s economic prosperity.

IECE Transactions on Social Statistics and Computing

ISSN: 2996-8488 (Online)

Email: [email protected]

Portico

All published articles are preserved here permanently:

https://www.portico.org/publishers/iece/